Alexandria Russell’s research on the memorialization of Black women led her closer to home than she could ever have imagined.

While attending graduate school at the University of South Carolina (UofSC), the Columbia native knew she was interested in researching Black women in public history. Through volunteer work with the nonprofit Historic Columbia, she learned about women who had made significant local contributions. Those women included Celia Mann, a free Black woman who lived in the city before the Civil War, and Modjeska Simkins, a 20th century social reformer and political activist.

During that period of discovery, Russell realized the critical role of Black women in her hometown.

But it wasn’t until she was completing her doctoral research that Russell discovered how the County has helped lead the charge to honor those women.

“African Americans have a rich public history presence throughout the nation, but particularly in Richland County,” she said. “It’s rich, it’s vibrant, it’s enduring, and you can easily have access to it, virtually or in person.”

Russell earned a Ph.D. in history from UofSC in 2018. Her dissertation, “Sites Seen & Unseen: Mapping African American Women's Public Memorialization,” involved researching memorials in large and small cities, towns and rural areas across the country.

With three traditional public history memorials and house museums, nine historical markers and an honorary street name within its limits, Richland County can claim 13 memorials honoring Black women – more than any other county in the nation, Russell concluded.

“I look at places near and far, so it was thrilling for me to discover that Columbia has such a significant place in the overall trajectory of Black women’s memorialization in the country,” she said.

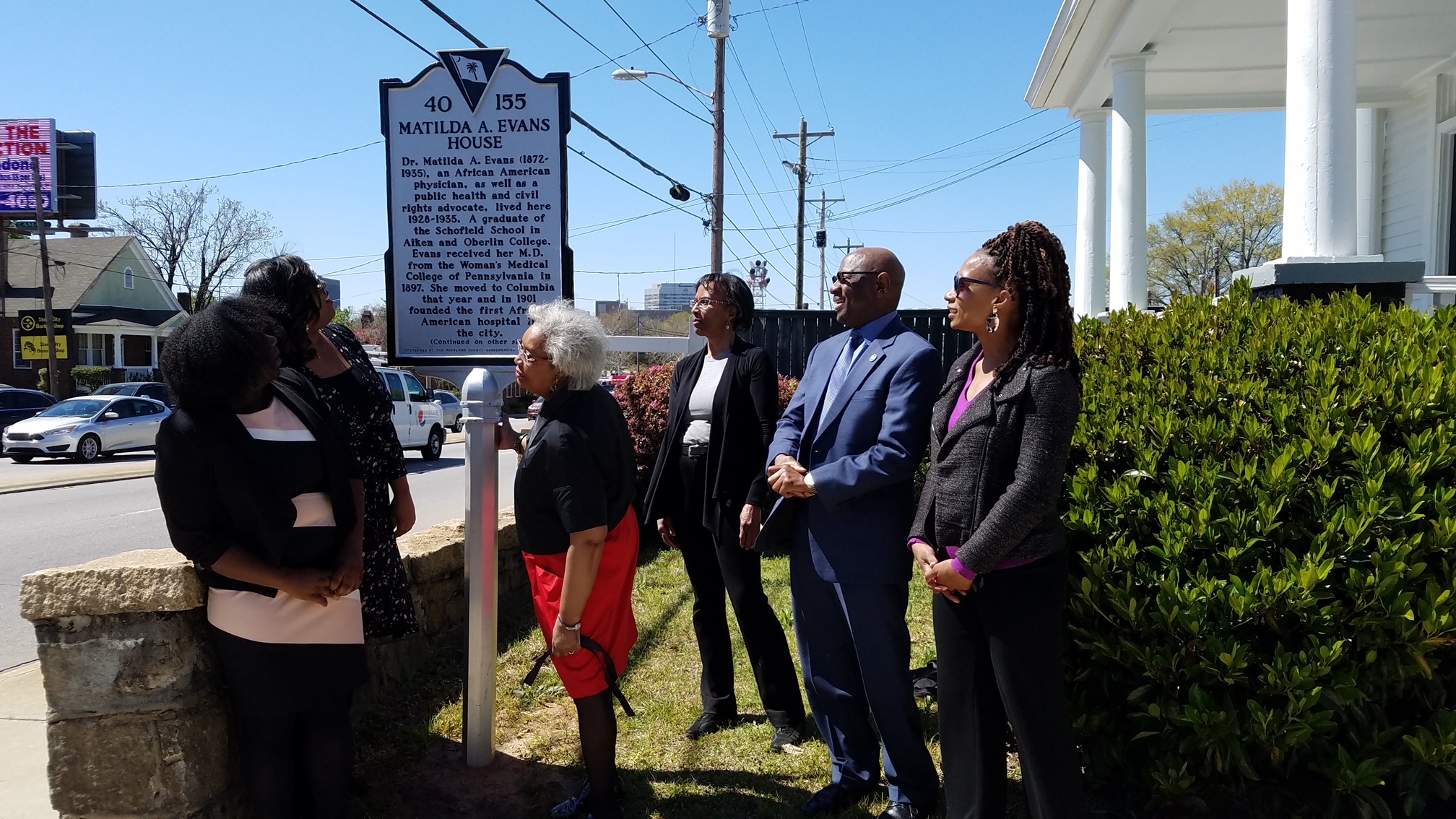

Richland County Council Chair Paul Livingston, second from right, attends the unveiling of a historical marker in 2019 at the Matilda A. Evans House on Taylor Street in Columbia. At left of the sign are Patrice Green, a University of South Carolina master’s student, and Alexandria Russell, who has researched memorials honoring Black women in Richland County. Fourth from right is Darlene Clark Hine, a retired professor who has researched Evans extensively.

Community Partnerships

In 1978, in an early sign of the County’s efforts to preserve Black women’s history, the surviving structure at the site of the Mann-Simons Cottage in downtown Columbia was opened as a house museum. Other preservation efforts followed, and since the late 2000s the County has made a pronounced shift toward recognizing African American women, according to Katharine Allen, director of research for Historic Columbia.

“It speaks quite clearly to what local leadership is doing, in terms of honoring individuals and showing that it’s important to honor women,” Allen said. “It’s also really important to honor these Black women who have made, by far, some of the greatest changes we’ve seen in the past 100-plus years.”

In recent years, the Richland County Conservation Commission (RCCC), Historic Columbia and other organizations have worked to memorialize Black women in the community, particularly by installing historical markers.

The South Carolina Historical Marker Program designates places important for understanding the state’s past, including the sites of significant events as well as historic buildings and structures. The markers can be sponsored and paid for by historical, patriotic, civic or other organizations, or by institutions such as churches, schools and colleges.

In Richland County, community members, most of them Black women, have reached out to historical organizations about noteworthy figures and sites in the area. In turn, those groups have helped research entities to get the memorials installed.

“Most of these projects are started by African Americans,” Russell said, “and then they are able to strategize and partner with larger organizations so they can maintain the site for a long period of time.”

The RCCC’s webpage on the Richland County website includes information on the installation process, as well as links to detailed descriptions of the markers sponsored by the RCCC.

Reginald Scott, the nephew of Harriet M. Cornwell, speaks at the unveiling of a historical marker at the tourist home named for Cornwell on Wayne Street in Columbia. The building housed African American tourists from about 1940 to about 1960.

Commission’s Role

Those RCCC-sponsored markers include several memorial projects that focus on Black women’s contributions.

The founding of the commission’s Historic Preservation Grants program helped restore the Harriet Barber House, a home for former slaves in Hopkins that has since received numerous grants from the RCCC. The commission has also provided grants for two other house-based museums: one for a new roof for the Mann-Simons Cottage and the other for an adjacent building and a reinterpretation at Simkins’ former home.

Of the County’s nine existing historical markers devoted to Black women, the RCCC has funded three – for the Harriet M. Cornwell Tourist Home, the Matilda A. Evans House and the Alston House.

Glenice Pearson, a former Richland County Conservation commissioner who remains involved in historic preservation efforts, can recall the role women played during the civil rights movement. While men often held leadership positions, many women stayed in the background and helped keep the movement alive, she said.

Going forward, Pearson aims to help the RCCC identify more Black women leaders across generations in Richland County – women whose achievements have gone unrecognized.

"There's a tremendous wealth of effort by women that has been overlooked simply because they may not have been in the limelight of the movements,” Pearson said.

“That's a big part of the job that we need to do moving forward, is to pull out of the shadows the work of Black women who really were the support system for all of the movements Black people had to engage in, in order to gain even a modicum of equal rights in our society,” she said.

Jettiva Belton, Holly Scott, Jean Hopkins and Dorothy Toney attend the unveiling of a historical marker for the former Columbia Hospital’s unit for Black patients and nursing students. All four women graduated from the Columbia Hospital School of Nursing between 1953 and 1965.

Carrying on a Legacy

Last October, a historical marker honoring the former Columbia Hospital’s segregated wing for Black patients and nursing students was unveiled at the Richland County Administration Building. Jean Hopkins, who graduated from the hospital’s nursing school before it closed in the 1960s, attended the ceremony in a nursing uniform from that era.

Hopkins said the school gave her a life as a nurse, and that the memorial, which was sponsored by the Columbia Hospital School of Nursing Alumnae Association of Black Nurses, represents an important time for her and many others. She said she hopes people who see the historical marker will learn about the school’s past and be inspired going forward.

“The history is carried on, and people can develop from it,” Hopkins said.

Richland County continues efforts to preserve Black women’s legacy in the community. The RCCC recently funded a historical marker to honor the Rollin Sisters, four mixed-race siblings who were involved in civil rights activism. The marker will be unveiled later this year in downtown Columbia.

Allen expects the County’s movement to memorialize Black women to continue and even gain traction in coming years.

“I think it’s only accelerating, because organizations like ours are working with scholars like Dr. Russell and seeing who else we might have missed so far,” Allen said. “That’s a really exciting aspect of the work that we do.”

Russell said she hopes new historic sites and markers honoring Black women make more people aware of the history surrounding them. She encourages Richland County residents to dig into local history and focus on stories of the women and places that often go unheard.

“I would encourage everyone to focus on (those stories) and to visit the sites that African American communities have made sure are here for us to visit,” Russell said.

##

Historical Markers Erected in Richland County

- Alston House – This Greek Revival cottage, built about 1872, was the residence and business of Caroline Alston, a Black businesswoman who lived and ran a dry goods store as early as 1873. She bought the house in 1888, becoming one of the few Black business owners in Columbia during the period. Near 1811 Gervais St., Columbia

- Blossom Street School/Celia Dial Saxon School -- Blossom Street School was built in 1898 as the first public school in Columbia and was originally a school for white children. It burned in 1915 and was rebuilt the next year. In 1929, the structure became a school for Black children; it was renamed Celia Dial Saxon School in 1930 in honor of Saxon (1857-1935), who taught in Columbia schools for 57 years and was a founder of the Wilkinson Orphanage, Wheatley YWCA and Fairwold Industrial School. On Blossom Street in Columbia, between Park and Assembly streets

- Columbia Hospital “Negro Nurses”/”Negro Unit” – The former Columbia Hospital built an expanded version of its segregated wing, or “Negro Unit,” in 1943 at the northwest corner of Harden and Lady streets, and in 1941 a three-story dormitory for Black nurses was built at Laurens and Washington streets. The hospital’s School of Nursing graduated more than 400 Black nurses before closing in the mid-1960s. At Harden and Washington streets, Columbia

- Harriet Barber House – In 1872, Samuel Barber and his wife, Harriet, both former slaves, bought 42

acres from the S.C. Land Commission, established in 1869 to give freedmen and freedwomen the opportunity to own land. A one-story frame house was built on the property about 1880. Barber was a farmer and minister after the Civil War. The Barber family still owns a major portion of this tract. On Lower Richland Boulevard near Barbershop Loop Road in Hopkins

acres from the S.C. Land Commission, established in 1869 to give freedmen and freedwomen the opportunity to own land. A one-story frame house was built on the property about 1880. Barber was a farmer and minister after the Civil War. The Barber family still owns a major portion of this tract. On Lower Richland Boulevard near Barbershop Loop Road in Hopkins

- Harriet M. Cornwell Tourist Home – The home’s first owner was John R. Cornwell, a Black businessman and civic leader who owned a successful barber shop on Main Street in Columbia. After his death, Cornwell’s wife, Hattie, and daughters Geneva Scott and Harriett Cornwell lived here. From the 1940s until after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 they ran the house as a “tourist home” for Black travelers. Near 1713 Wayne St., Columbia

- Mann-Simons Cottage – This structure, built before 1850, was the home of Celia Mann (1799-1867) and her husband, Ben Delane, among the few free Black people living in Columbia in the two decades before the Civil War. Mann, born a slave in Charleston, earned or bought her freedom in the 1840s and moved to Columbia, where she worked as a midwife. Three Baptist churches (First Calvary, Second Calvary and Zion) trace their origins to services held in the basement of this house, which has been a museum since 1977. 1403 Ridgeland St., Columbia

- Matilda A. Evans House – Dr. Matilda A. Evans (1872-1935), a Black physician as well as a public health and civil rights advocate, lived at this location from 1928 to 1935. A graduate of the Schofield School in Aiken and Oberlin College, Evans received her medical degree from the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1897. She moved to Columbia that year and in 1901 founded the city’s first African American hospital. She later opened St. Luke’s Hospital & Training School for Nurses, served in the U.S. Army Sanitary Corps during World War I and founded the S.C. Good Health Association. Near 2027 Taylor St., Columbia

- Modjeska Simkins House – For 60 years, this was the home of Modjeska Monteith Simkins (1899-1992), a social reformer and civil rights activist. A Columbia native, she was educated at Benedict College, then taught high school. As director of Negro work for the S.C. Anti-tuberculosis Association (1931-1942), Simkins was the first Black person in South Carolina to hold a full-time, statewide, public health position. She founded the S.C. Conference of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Near 2025 Marion St., Columbia

- Monteith School – This African-American school, built before 1900, was originally New Hope School, a white school affiliated with Union Church. It closed about 1914. In 1921, Rachel Hull Monteith opened Nelson School as a Black public school in the Hyatt Park School District. It later became a three-teacher school with Monteith as its principal. Nelson School was renamed Monteith School in 1932. A civil rights activist, Monteith was the mother of civil rights activist Modjeska Monteith Simkins. Near 6510 Main St., Columbia

Traditional public history memorials/house museums (see list above)

- Celia Mann-Simons Site

- Harriet Barber House

- Modjeska Simkins House

Honorary street name

Sarah Mae Flemming Way – On June 22, 1954, Sarah Mae Flemming (1933-1993) took a seat near the front of a segregated city bus. Expelled from the bus, Flemming sued the bus company. In federal court in Columbia and then in U.S. Circuit Court, Flemming endured humiliation and argued against segregation on Columbia buses. She won her case, and her efforts served as the foundation for the 1956 Browder v. Gayle U.S. Supreme Court case, sparked by Rosa Parks’ unwillingness to give up her seat on a city bus in 1955 in Birmingham, Ala. With Browder v. Gayle, the high court ruled bus segregation to be unconstitutional. 1100 block of Washington Street, between Main and Assembly streets, Columbia

Historical marker (unveiling TBA)

Rollin Sisters – Mixed-race sisters Frances Ann “Frank,” Katherine, Charlotte, Marie Louise and Florence Rollin were born in Charleston but eventually settled in Columbia. All of the sisters were involved in civil rights activism, with Charlotte speaking before the S.C. House of Representatives in 1869 to plead for women’s suffrage and Charlotte and her sisters organizing a Women’s Rights Convention in 1870. Afterward, the sisters received a charter for a state branch of the American Woman Suffrage Association, a coalition that worked for universal suffrage regardless of gender or race. Later, the sisters’ “Rollin salon” business at Senate and Sumter streets became known for its interracial gatherings supporting social causes.

##